[Book Review] Courageous Marketing: The B2B Marketer's Playbook for Career Success Book by Udi Ledergor.

The first chapter opens with a line from Robert Kiyosaki, quoted as if it were bedrock philosophical truth: “Often, in the real world, it’s not the smart that get ahead but the bold.” Yet readers familiar with Kiyosaki’s legacy—particularly in Asian markets—often learn the hard way that his prescriptions work only within a very specific American context. Buying versus renting real estate, for example, reverses its logic entirely depending on the geography in question.

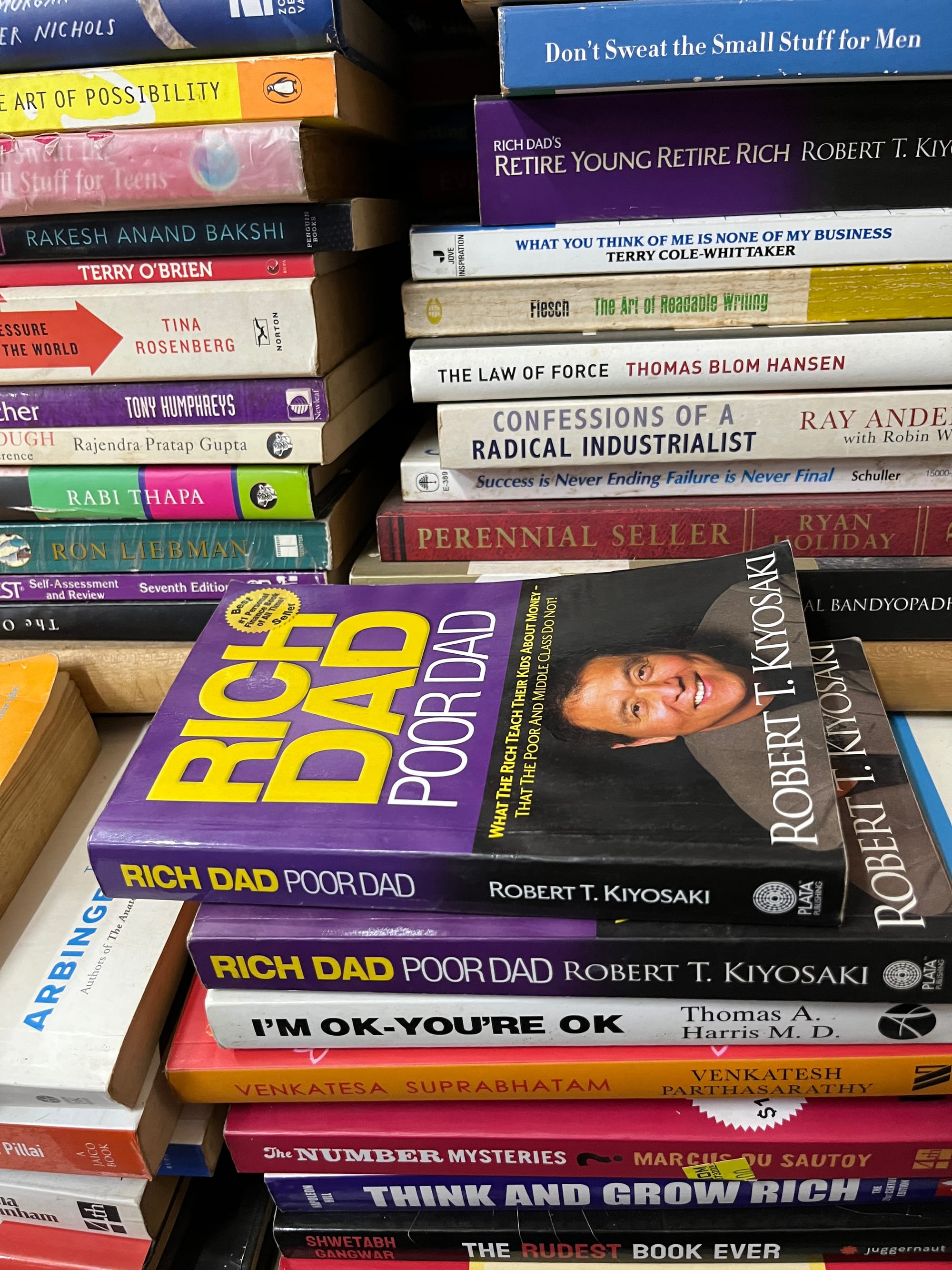

That’s the trouble with universal slogans: they rarely survive contact with the real world. And as the chapters unfold, the book’s marketing advice falls into the same trap—offering broad, declarative lessons that depend heavily on where a company is built, whom it sells to, and how its market behaves. Much of Courageous Marketing reads like an enthusiastic scrapbook of American B2B marketing stories delivered as if they represent universally reliable truths.

A more fitting warning label for the entire text might be:

“Highly effective in certain Silicon Valley conditions; results may vary elsewhere.”

A Super Bowl, a Billboard, and the Geography Problem

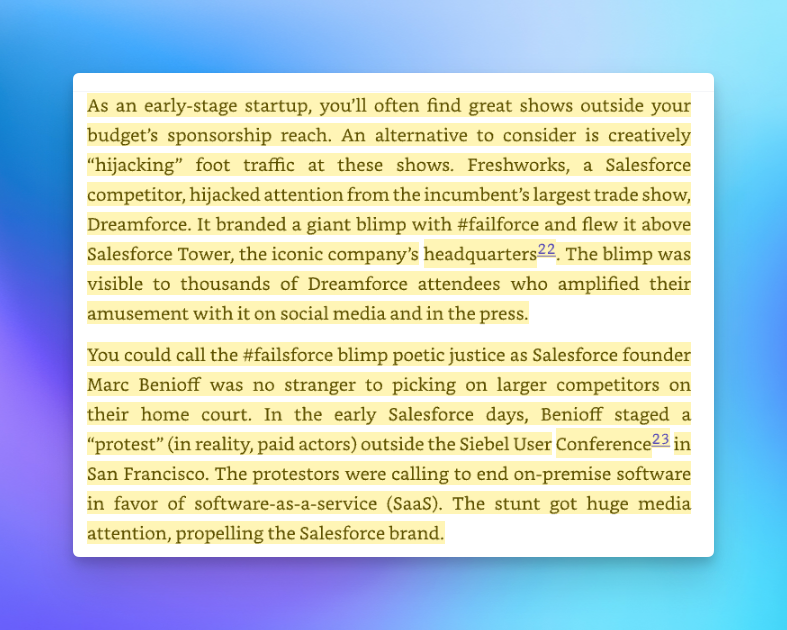

The book’s introductory case study revolves around a Super Bowl commercial—an iconic but decidedly American cultural moment. The author moves seamlessly from football stadiums to Times Square billboards, describing how a brief NASDAQ slot became a marketing triumph. For marketers operating in Europe, Southeast Asia, or anywhere outside the United States, these anecdotes feel distant, almost out of place.

Times Square billboards, once signifiers of glamour and reach, have now become a kind of corporate selfie backdrop—impressive on LinkedIn but often meaningless in terms of customer value. And yet the book celebrates such stunts as if they form a universal marketing playbook.

Context is everything. A stunt that resonates with American sales teams or U.S.-centric SaaS buyers may fall flat—or appear bewildering—when translated into Asian or European markets.

The narrative rarely acknowledges this.

Committee-Based Marketing: A Problem Well Known But Poorly Explored

One of the early warnings in the book is about “committee-based marketing,” illustrated with the observation that consensus tends to dilute creative boldness. As the text notes, “the focus is naturally on consensus and compromise,” and over-involving stakeholders leads to “appeasing each individual by watering their input” into mediocrity.

This is not untrue, but it is also not new.

Large teams, cross-functional approvals, and risk aversion are familiar realities for mid-size and enterprise companies. What’s missing is guidance on navigating those politics—how to persuade, negotiate, prioritise, and survive the organizational labyrinth. The book identifies the symptoms but does not offer a cure.

The One-Hit-Wonder Pattern

The text repeatedly celebrates case studies from Drift and Dave Gerhardt, presenting them almost as canonical scripture. The issue is not their success but the assumption that these are universally transferable. Marketing strategies that thrived for a particular product, in a specific American market, during a specific era may not hold up across different sectors or regions.

This is the recurring analytical gap: single-instance success stories presented as universal wisdom.

When examples come exclusively from the same cluster of San Francisco–born SaaS products, the conclusions inevitably become narrow. The tone suggests a confidence that these tactics can be ported seamlessly to cybersecurity firms, enterprise infrastructure tools, or startups selling into european procurement cycles—a premise that rarely survives reality.

Category Creation: A Rallying Cry Without Grounding

Few topics in modern marketing generate as much performative enthusiasm as “category creation.” The book leans heavily into this idea, framing it as a bold path for ambitious companies. But when stripped of rhetoric, category creation often becomes an exercise in branding jargon rather than customer value.

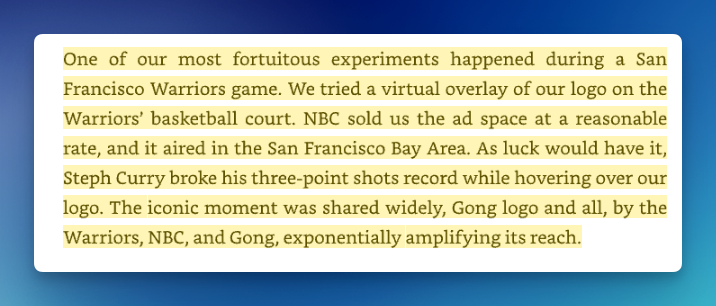

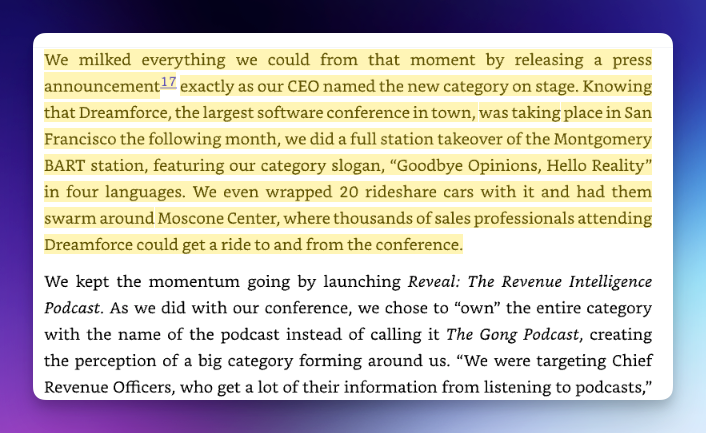

The text cites Gong’s fusion of a “mature” enterprise space with a “friendly” tone, treating this stylistic shift as a form of category breakthrough. But outside certain U.S. markets, such whimsicality can seem out of place—sometimes even counterproductive.

In most real-world contexts, deeply understanding a product, improving it meaningfully, and articulating its value clearly matter far more than constructing a fancy new label for it.

When Courage Becomes Carelessness.

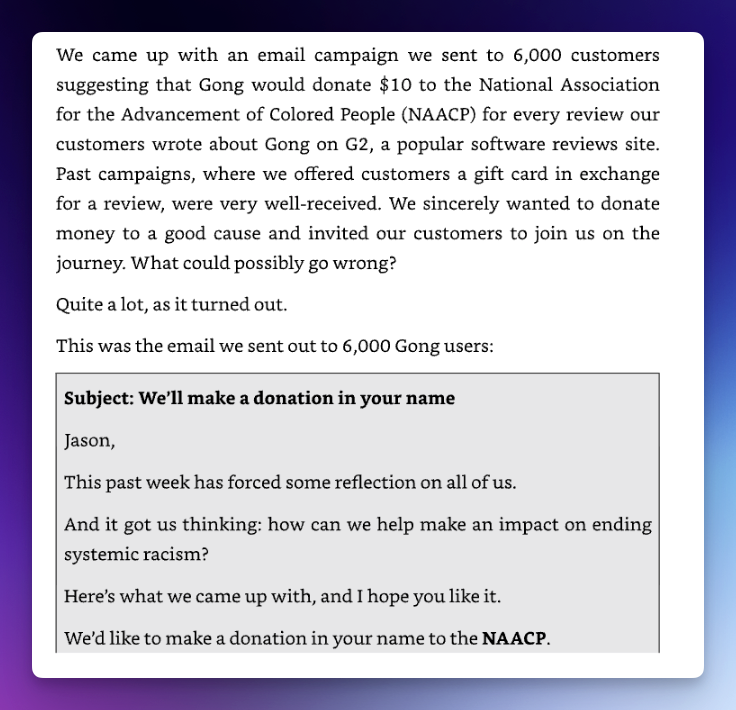

Midway through the book lies a case study that reveals its most unsettling blind spot: an email campaign launched in the days following the murder of George Floyd. The company promised to donate $10 to the NAACP for every new review posted on G2. The response, predictably, was swift and negative—from customers, investors, and the broader community. An apology email followed, beginning with “I messed up.”

The unsettling part is not the mistake itself—marketers misread moments all the time—but the framing. The book recounts the apology as a kind of brand-recovery triumph, emphasizing how quickly reputational damage was repaired. What remains unaddressed is the fundamental misjudgment: how such an emotionally tone-deaf idea survived internal discussions in the first place.

The story is presented almost as a badge of courage. It reads more like an indictment of marketing tunnel vision.

Long-Term Consequences and the Jack Welch Parallel

The text’s short-term stardust often obscures long-term consequences. A striking parallel emerges in the reference to Jack Welch, once glorified as a management icon. Two decades later, his obsession with shareholder value is widely viewed as having harmed innovation and resilience, a shift chronicled in David Gelles’s The Man Who Broke Capitalism.

The caution here is simple: flashy marketing wins can be seductive in the short term, but their true impact is visible only years later. Many of the companies showcased in the book have since been acquired, faded from memory, or lost momentum. Yet the anecdotes are delivered as if they carry timeless significance. The author should have added enough warning labels.

Where the Book Actually Succeeds?

Despite its limitations, the book is not devoid of insight.

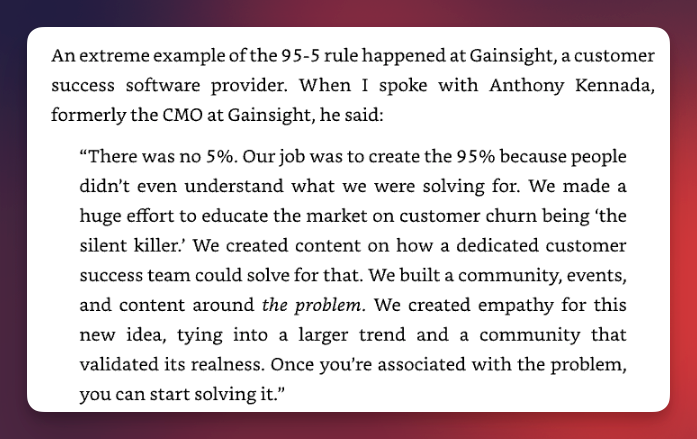

The explanation of the “95–5 rule” stands out—a recognition that most buyers are not actively in-market, and marketing must educate long before it sells. It’s one of the rare sections that acknowledges cognitive reality rather than relying on spectacle.

The emphasis on content written by genuine subject-matter experts is equally sound. Content grounded in lived industry experience has a texture and credibility that generic writing cannot match.

The endorsement of early marketing ops hiring is also practical, not performative—allowing teams to focus on strategic thinking rather than drowning in tool configurations.

Finally, the idea of the T-shaped marketer—broad across functions but deep in one—remains valuable career advice, applicable across regions and industries.

Chasing The Product–Market Fit: I disagree with every word of this chapter.

One of the book’s more discouraging assertions is that marketers should avoid companies without product–market fit—that joining a pre-PMF team is career risk. The implication is that marketers should wait for the product to “work” before participating in its story.

But the hardest, richest marketing lessons almost always emerge before PMF—during the years of experimentation, customer discovery, ambiguity, false starts, and small wins. That phase is where true understanding forms: of customers, product nuances, market resistance, and messaging that evolves from lived reality rather than hindsight.

Suggesting that marketers only join companies at comfortable stages turns the craft into performance rather than practice.

The Book’s Real Limitation: It Speaks to Only One World

The final chapters make the book’s limitation undeniable: its worldview is shaped almost entirely by the vantage point of a San Francisco–based SaaS ecosystem with abundant venture capital, mid-ticket pricing, American buyers, and easy access to high-visibility stunts.

The text rarely addresses whether these tactics translate to engineering-focused products, to privacy-conscious European markets, or to fast-growing Asian ecosystems where frugality, trust-building, and technical validation often outweigh theatrics.

Many of the examples read like LinkedIn posts—sharp, punchy anecdotes detached from broader context and assembled into chapters without the connective tissue required for a true playbook.

Conclusion

Courageous Marketing is not a bad book so much as a geographically narrow one—written with confidence, crafted with enthusiasm, but unaware of its own limitations. It shines when discussing fundamentals: content, expertise, early structure, and market education. But when it ventures into stunts, proclamations, and exceptionalism, it falters—not because the stories are untrue, but because they are presented as universally applicable.

Marketing courage is not found in billboards, blimps, or viral stunts. It lives in the slow, unglamorous work of understanding markets, iterating with imperfect products, and building trust across cultures and constraints.

Most marketers don’t have Times Square or the Super Bowl at their disposal.

What they have is context—and context matters far more than boldness.

Despite Udi Ledergor’s stature as a five-time marketing leader, the book ultimately feels lighter than expected. His reputation was the very reason the book seemed worth picking up—an operator with years of experience, someone who has seen teams built from scratch, scaled, reorganized, and tested under pressure.

With that background, one would imagine the pages might dive into the gritty, unglamorous mechanics of marketing: how budgets are shaped, how a team grows from one person to a department, how metrics are chosen and interpreted, how customer feedback moves through an organisation and into product decisions, or how an ideal customer profile is actually built beyond buzzwords. These are the kinds of lessons that don’t live on Google search results—the ones that come only from years in the trenches.

Instead, the book gravitates toward the spectacle. It lingers on the bold moves, the showmanship, the now-famous anecdotes that photograph well on a conference slide. The tactical depth—the pieces that would help a marketer at any company, in any geography—never quite arrives. That gap is where the disappointment settles: a book by an experienced operator that rarely opens the door to the operator’s room.