[Book Review] "The Art of Slow Writing," Louise DeSalvo

In "The Art of Slow Writing," Louise DeSalvo challenges the modern rush to produce, advocating instead for a deliberate and patient approach to the craft.

DeSalvo draws on the habits of legendary writers like Virginia Woolf, Ernest Hemingway, and Anne Tyler to reveal how great work emerges from consistent practice, deep reflection, and meticulous revision.

The book highlights practical methods used by renowned authors, from meticulous revision and reading with a pen to keeping notebooks for gathering ideas. DeSalvo emphasizes the importance of deliberate practice, deep reflection, and actively protecting one's writing time.

It’s a reminder that writing is as much about sculpting a life that supports the craft as it is about putting words on the page. For anyone feeling rushed or stuck, DeSalvo’s insights offer both permission and practical tools to embrace the journey, not just the destination.

Some excerpts from the book

As Roxane Gay has written in Salon, we have a “cultural obsession with genius.” Yet the best writing grows by accretion, over time. As John Updike said, “I try to be a regular sort of fellow— much like a dentist drilling his teeth every morning —except Sunday....” It allows us to understand that creating fine work can only be achieved by a slow, consistent dedication to our craft.”

“I love visiting writers’ houses. I imagine a writer sitting at a desk; taking time to craft each sentence of a work in progress; living the unhurried, unharried writer’s life I desire, the one I try (sometimes successfully, sometimes not) to enact myself.”

“Publishers now act as if writing is the same as typing.”

“When Tyler is satisfied, “she types it up, then writes the whole manuscript out in longhand again.” She then “reads it into a tape recorder to listen for false notes or clumsiness.” Instead of retyping, she “plays it back ... on a stenographer’s machine with a pedal to pause” so she can insert material.

“Let’s say that in assessing a memoir in progress, we discover we don’t describe place—we write as if the events could have taken place anywhere. So we devise structured activities to improve. We choose a novel or memoir that treats place brilliantly, and we study twenty pages, underlining instances where the writer describes place and its impact on character. We copy key passages— copying is an excellent device to improve our work. Then we analyze when that writer used setting and how it affects the work’s meaning.”

“I’ve written about the advantages of keeping a process journal. But there’s another kind of journal —Joan Didion calls it a notebook—that’s important for writers, too. Into her notebook, Didion writes descriptions of people she observes, random observations (the sign on a coat in a museum), facts she’s learned (the tons of soot that fell on New York in 1964), recipes (one, for sauerkraut). Didion doesn’t necessarily draw from this notebook in her work. But she believes it’s important for her as a writer to remember what she’s experienced, and the only way to do that is to keep a written record.

“Rush’s example illustrates the virtue for writers of carrying notebooks everywhere and recording whatever seems important at the time, even without knowing its potential use. Isabel Allende keeps a notepad by her bedside to collect material that comes to her in dreams. Margaret Atwood thinks writers “should carry notebooks with them at all times just for those moments because there’s nothing worse than having that moment and finding that you’re unable to set it down except with a knife on your leg or something.” Atwood also loves “sticky notes,” and she, too, keeps a “bedside notebook” for gathering material that she might use in her work”

“Woolf improved her prose by setting herself reading programs. She didn’t just read; she read with pen in hand to improve her work. She read to learn how to write scenes, describe landscape, construct image patterns, depict the passage of time. She kept notebooks in which she evaluated what she read and copied passages that helped her learn her craft”

“I’ve learned that Anthony Trollope, author of forty-seven novels, among them, Barchester Towers (1857), employed a similar process. “When I have commenced a new book,” Trollope wrote, “I have always prepared a diary, divided into weeks, and carried it on for the period which I have allowed myself for the completion of the work.” Into this diary, Trollope recorded his progress so that if he slacked off, “the record of that idleness has been there, staring me in the face, and demanding of me increased labor.”

“I learned how to write prose by hand-copying more than a thousand pages of Woolf’s drafts of The Voyage Out (1915), her first novel. This taught me to slow down to see how a writer at work constructs sentences, paragraphs, and scenes. I learned how to revise by studying what Woolf deleted, added, or changed. I never before understood how much published writers revised.”

“Ernest Hemingway kept something like a ship’s log. In interviewing him, George Plimpton learned that Hemingway kept track “of his daily progress—‘so as not to kid myself’—on a large chart made out of the side of a cardboard packing case and set up against the wall under the nose of a mounted gazelle head.” On the chart, Hemingway recorded his “daily output”: “450, 575, 462, 1250, back to 512,” the high number reflecting days Hemingway worked longer so he could spend the next day “fishing on the Gulf Stream.”

“Throughout composing his first draft, McEwan works slowly, and he works meticulously, pretending the “first draft is the last.” This saves him difficulty when he’s completing his work. He reads his work aloud, paragraph by paragraph. And then he thinks of “the chapter as an intact, independent entity with a distinct character of its own, a kind of short story”—the chapter is an “important building block” of his work and McEwan ascertains whether his chapters are meeting those criteria.

“My students are often stunned to learn that famous writers revise more and take longer to complete their works than my students think necessary. Ernest Hemingway penned about fortyseven alternate endings of A Farewell to Arms (1929) before deciding on the one he used.

“Woolf usually wrote fiction for two and a half to three uninterrupted hours, from about ten in the morning to twelve thirty or one in the afternoon. Did she write a thousand words, two thousand? I opened the early draft of To the Lighthouse to May 9, 1926, and learned that Woolf penned roughly 535 words and crossed out 73 of them, netting her 462 words for her day’s work. Let’s say she worked for three hours. That’s about 178 words an hour including the words she deleted—and Woolf was writing at the height of her creative powers.”

“By the end of the first week, I felt as if I’d found the reader in myself I’d lost many years ago. The reader who wept over a passage. Who laughed out loud. Who circled back to the beginning of a book to start it all over again. Who marveled at the brilliance of a phrase, of a sentence, of a long stretch of writing. Who sat and stared at the sky in astonishment, recalling something wondrously written.

“All of us can write. Few of us know how to work at writing. And even fewer of us know how to sculpt our lives so we can write. These are learned skills, acquired through time and practice. And, Hallowell says, it seems more difficult to practice these skills now, because learning how to think deeply about our writing lives is different from just being busy. Reflection takes time, quiet, and patience.”

“Tyler doesn’t begin from scratch. She keeps “an index box in which she has written ideas ... and left them to ripen for years ... until she feels she can make something of it.”

Later, if she had time, she’d read her work and plan what came next. “If you write two pages a day,” Shields said, “you have ten pages at the end of the week. At the end of a year, you have a novel, and I did have a novel.” Shields was surprised that “these writings, these little segments, added up to something larger”

“I protect my writing time. I don’t engage in long telephone conversations, lunches with people I don’t love, most meetings, Facebook, net surfing, e-mailing more than once a day, shopping for the sake of shopping, boozy nights out, television (except for movies), most parties, readings.

I spend some time in a cost-benefit analysis of the opportunities that come my way. Do I really want to do it? What will it cost? What will I gain? If the cost outweighs the gain, I don’t do it.

“Carey prepares for his novels by using index cards and divides them into chapters. He thinks of each chapter as a room, and he asks himself “what happens within each room.”

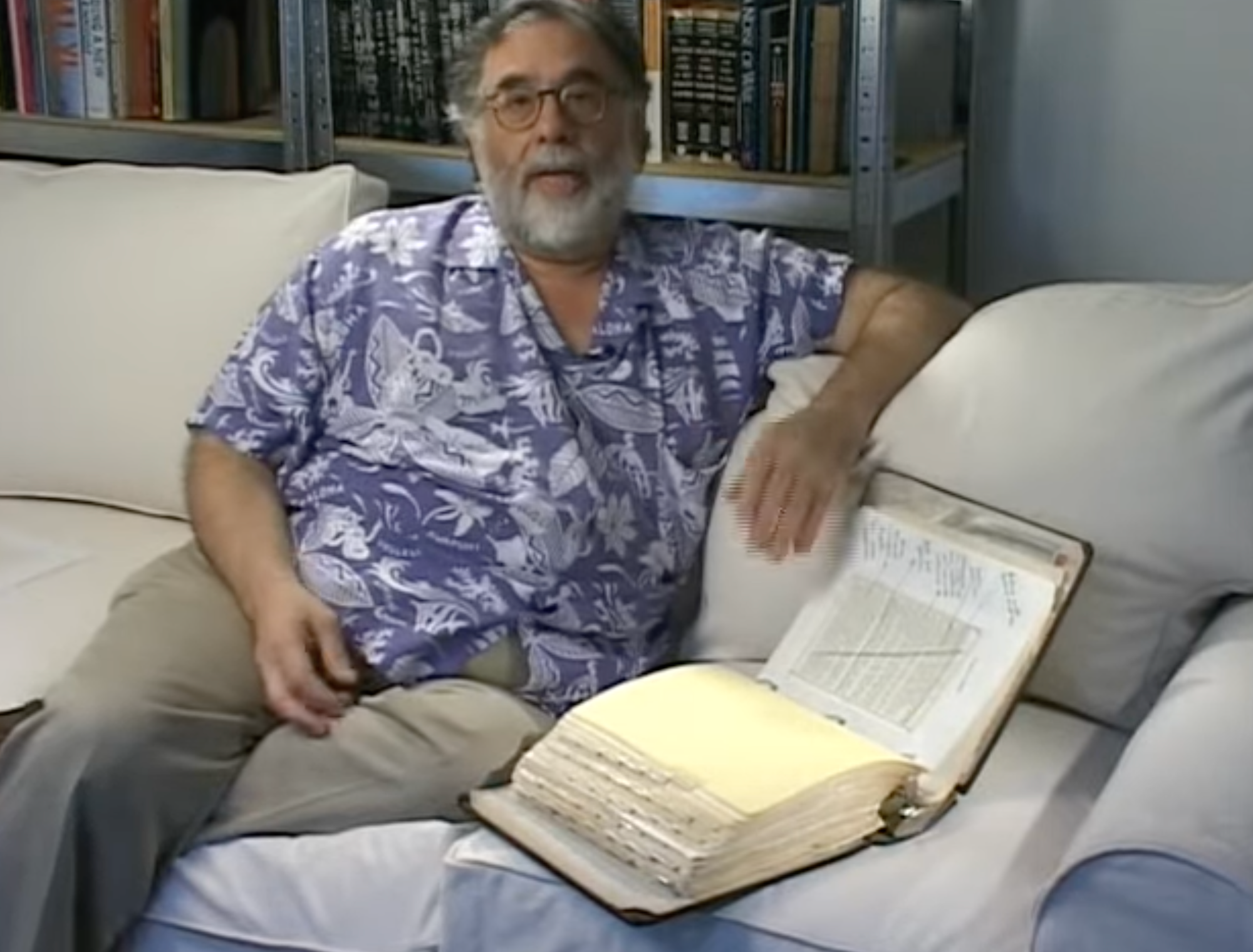

Carey has drafts of his novels “bound into what he calls ‘working notebooks,’” his personal version of a writer’s mise en place. He highlights the places in the work “where further research is necessary.” In the margins, Carey affixes “chapter plans and plot points, calendars and timelines, and occasionally pasted-in postcards—anything relevant to the story in progress.” The notebooks permit Carey to interweave his research with “his own richly invented worlds.” Because everything he needs to rewrite and revise his draft is at his fingertips.

Colvin outlines five key elements of deliberate practice.

- First, deliberate practice is “designed specifically to improve performance” and move us beyond our current abilities. We identify elements of our work that need development. We isolate one, structure activities designed to help us improve, then move on to the next.

- Second, deliberate practice must be repeated.

- Third, deliberate practice requires feedback about our progress from a mentor or writing partner.

- Fourth, deliberate practice demands focus and concentration; it must be undertaken slowly for short sessions.

- Fifth, deliberate practice isn’t fun